2/3

TEENS AND SPORTS: WHEN PRESSURE TAKES THE JOY OUT OF THE GAME

2/3

TEENS AND SPORTS: WHEN PRESSURE TAKES THE JOY OUT OF THE GAME

Co-author: Véronique Boudreault, PhD, PsyD, professor at Université de Sherbrooke and holder of the Aléo research chair

Sports can be a powerful driver of well-being for young people: they build confidence, reinforce a sense of belonging, and improve physical and mental health. However, they can also have mixed effects on mental health.

Behind the adrenaline rush of competitions and moments of pride sometimes lie heavier emotions: fear of disappointment, exhaustion, performance pressure, anxiety . . .

As a parent, relative, coach, or caregiver, you play a key role in supporting the young people in your life. This second article in our series on sports and mental health will help you spot the signs of psychological distress in young athletes and understand where performance anxiety comes from, so you can help them manage it more effectively.

👉 Related reading: The first article in our series. Discover the benefits of physical activity for young people’s mental health and development.

Play on: The positive impact of sports on teensIn collaboration with CF Montréal

STRESS VS. ANXIETY: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE? 🤔

Although they’re often seen as interchangeable, stress and anxiety are two distinct phenomena.

💡Stress is a normal, temporary response to a situation that is perceived as threatening or dangerous (like a competition, exam, or team change). It allows us to quickly mobilize the energy and resources needed to overcome a challenge, then dissipates once the situation is over.1

💡 Anxiety, on the other hand, is an emotion related to the anticipation of a future threat, often one that is imagined or exaggerated. It triggers the same physiological responses as stress (muscle tension, accelerated heart rate, heightened alertness), but in a more persistent and pervasive way, even in the absence of any real threat. It manifests as excessive worry, fatigue, and trouble sleeping, and can interfere with concentration, motivation, and enjoyment.19

STRESS: A NORMAL, HELPFUL RESPONSE—TO A POINT

It’s perfectly normal to feel stressed before a performance. Stress can boost concentration, energy, and motivation.9 Even world-class athletes deal with performance stress!

But bear in mind:

When this pressure becomes constant and excessive, it can impair performance and well-being, leading to symptoms such as:

- Fatigue

- Disrupted sleep

- Reduced motivation

- Increased risk of injury10

The earlier you recognize these signs, the easier it will be to intervene and use the appropriate regulation strategies.

WHEN CAN SPORTS BECOME A SOURCE OF PERFORMANCE ANXIETY?

The anxiety experienced by young athletes can stem from expectations that exceed the teen’s abilities (or when pressure outweighs pleasure):

😞 Fear of disappointing others

If a teen believes that they have to earn their parents’ or friends’ approval through their athletic performance, they may feel like they’re under a lot of pressure to succeed.3

Without realizing it, you may be doing things that make your teen feel obligated to succeed.4 This could look like, for example, only talking about their athletic performance or investing a lot of time and money in their sports career. The result? Stress, guilt, or a constant fear of failing to meet expectations.5

🥉 Fear of failure

In a highly competitive environment, not making the team or missing an important goal can be a real source of anxiety.6

In adolescence, peer recognition plays a central role in self-esteem. As sports are often a way to gain social clout, young people who excel at their sports may have a higher social standing, while others may feel excluded or less popular.7 This pressure to perform can quickly undermine their self-confidence.

📱 Social media

Every day, teenagers see an idealized version of what success looks like, including perfect bodies and unrealistically good performances.

This constant comparison can make their anxiety worse, feed into feelings of inferiority, and damage their self-esteem.

🎢 Transition periods

Changing teams, moving up a level, or dealing with an injury: All of these are moments of uncertainty that can be destabilizing.8

Without adequate support, these challenges can make young athletes feel stressed, less motivated, and out of balance.

GOOD STRESS OR BAD STRESS?

In order to develop coping and anxiety management strategies, and turn stress into a help rather than a hindrance, it’s essential to understand the difference between functional and dysfunctional stress:

👉 Functional stress is a natural, adaptive response that is beneficial because it enhances concentration and effort, improving performance. It is often felt before a competition, in the form of excitement or physiological activation, but generally fades during the activity.

👉 Dysfunctional stress, on the other hand, occurs when an athlete perceives a situation as a threat rather than a challenge. Their stress turns into paralyzing anxiety. They may feel excessive self-doubt, want to avoid competitions, or ruminate on past errors.11 When not properly managed, dysfunctional stress can affect teens’ mental well-being and increase the risk of dropping out of their sport.

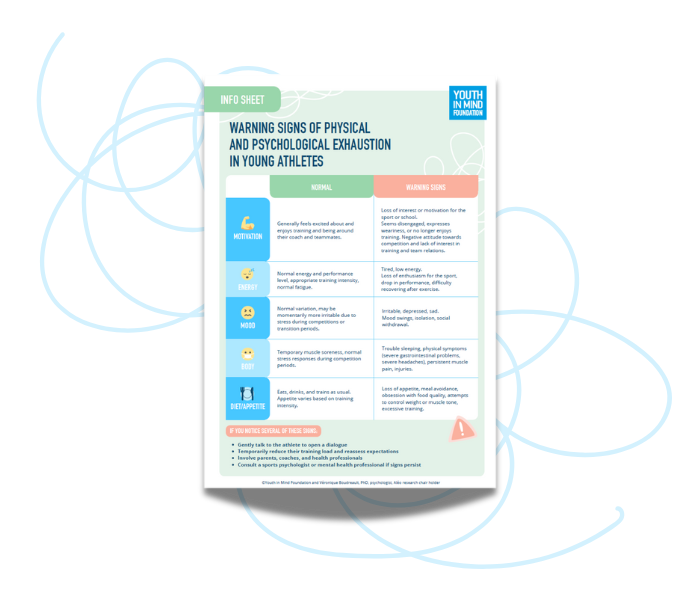

RECOGNIZING SIGNS OF DISTRESS IN A YOUNG ATHLETE

As parents, coaches, or loved ones, we need to be aware of the following warning signs:

🚩 Loss of motivation

A previously enthusiastic teenager suddenly seems disengaged, expresses weariness, or no longer enjoys training.12 This lack of motivation may be accompanied by low energy, a negative attitude toward competition, or a lack of interest in training and team relations.

🚩 Excessive fatigue

Overtraining, constant pressure, or a lack of adequate recovery can lead to physical and mental exhaustion. This can result in a drop in performance and a loss of enthusiasm for the sport.13

🚩 Marked anxiety

While a certain amount of stress can improve performance, excessive anxiety can become paralyzing. Young athletes in distress may experience intense pre-competition anxiety and a heightened fear of failure, sleep problems, increased irritability, or physical symptoms (severe gastrointestinal problems, severe headaches).14

🚩 Eating disorders and excessive preoccupation with body image

In some sports (aesthetic sports, endurance sports, and sports with weight categories) where the pressure to meet aesthetic standards is extreme, young athletes can develop a negative body image and disordered eating behaviours.15

Avoiding meals, an obsession with food quality, attempts to control weight or muscle tone, and excessive training are often warning signs of eating disorders.16

🚩 Social isolation and depression

A young person who self-isolates, avoids social situations, or is experiencing mood swings, increased irritability, or persistent sadness may be depressed.17

If these symptoms persist, it’s important to take the situation seriously and offer appropriate support. Untreated psychological distress can lead to reduced performance, gradual disengagement from sports, and even an increased risk of injury and long-term health problems.18

📌In the info sheet below, you’ll find a summary table of warning signs of physical and psychological exhaustion in young athletes.

Remember that looking out for your teen doesn’t mean controlling them. The teen years are a crucial waypoint on the road to independence, and it’s important to support your teen’s development by encouraging them to reflect on and discuss their life balance.

If you notice signs that worry you, simply share what you observe, keeping to the facts, and express your concern in a caring way. Then work with them to identify adjustments that can be made and find out if they need help implementing them.

Download info sheetHOW TO SUPPORT MENTAL HEALTH AND BALANCE IN YOUNG ATHLETES

🎯 This will be the focus of the third article in this series, in which we’ll explore concrete strategies for supporting young people in their athletic careers while protecting their mental health.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

In collaboration with

Sources

1S.J. Lupien, I. Ouellet-Morin, A. Hupbach, et al., “Beyond the stress concept: Allostatic load—a developmental biological and cognitive perspective,” in Developmental Psychopathology: Volume Two: Developmental Neuroscience, ed. D. Cicchetti (Wiley, 2015) pp. 578–628.

R.S. Lazarus and S. Folkman, Stress, appraisal, and coping. (Springer, 1984).

2American Psychological Association, “Anxiety,” in APA Dictionary of Psychology https://dictionary.apa.org/anxiety.

3C.G. Harwood and C.J. Knight, “Parenting in youth sport: A position paper on parenting expertise,” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 16, no. 1 (2015): 24–35.

4T.E. Dorsch, A.L. Smith, and A.M. Dotterer, “Individual, relationship, and context factors associated with parent support and pressure in organized youth sport,” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 23 (2016): 132–141.

5M.R. Atkins, D.M. Johnson, E.C. Force, and T.A. Petrie, “Do I still want to play? Parents’ and peers’ influences on girls’ continuation in sport,” Journal of Sport Behavior 36, no. 4 (2013): 329–345.

6A. Gledhill, C. Harwood, and D. Forsyke, “Psychosocial factors associated with talent development in football: A systematic review,” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 31 (2017): 93–112.

7H. Jõesaar, V. Hein, and M.S. Hagger, “Peer influence on young athletes’ need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and persistence in sport: A 12-month prospective study,” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 13, no. 5 (2011): 500–508.

8N. Stambulova, T.V. Ryba, and K. Henriksen, “Career development and transitions of athletes: The International Society of Sport Psychology position stand revisited,” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 19, no. 4 (2020): 263–289.

9S. Hanton, S.D. Mellalieu, and R. Hall, “Self-confidence and anxiety interpretation: A qualitative investigation,” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 5, no. 4 (2004): 477–495.

10R. Arnold and D. Fletcher, Stress, Well-Being, and Performance in Sport (Taylor and Francis, 2021), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429295874.

11Y. Ramis, M. Torregrossa, C. Viladrich, and J. Cruz, “The effect of competition stressors on sport motivation: A self-determination theory approach,” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 31 (2017): 77–85.

12R.J. Schinke, N.B. Stambulova, G. Si, and Z. Moore, “International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development,” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 16, no. 6 (2017): 622–639.

13H. Gustafsson, G. Kenttä, and P. Hassmén, “Burnout in competitive and elite athletes: A systematic review,” The Sport Psychologist, 25 no. 4 (2011): 512–536.

14S.M. Rice, M. Butterworth, M. Clements, P. Joshi, and R. Purcell, “Development and implementation of the national mental health referral network for elite athletes: A case study of the Australian Institute of Sport,” Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology 3 no. 1 (2019): 1–10.

15V. Boudreault, M.-P. Gagnon-Girouard, N. Carbonneau, S. Labossière, C. Bégin, and S. Parent, “Extreme weight control behaviors among adolescent athletes: Links with weight-related maltreatment from parents and coaches and sport ethic norms,” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 57 no. 3 (2022): 421–439, https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902211018672.

16D.K. Voelker, T.A. Petrie, J.J. Reel, and D. Gould, “Frequency and psychosocial correlates of eating disorder symptomatology in male figure skaters,” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 30, no. 1 (2017): 119–126, https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1325416.

17R. Purcell, K. Gwyther, and S.M. Rice, “Mental health in elite athletes: Increased awareness requires an early intervention framework to respond to athlete needs,” Sports Medicine – Open 6, no. 1 (2019): 46.

18K. Henriksen, R. Schinke, K. Moesch, S. McCann, W.D. Parham, C.H. Larsen, and P. Terry, “Consensus statement on improving the mental health of high performance athletes,” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 18, no. 5 (2019): 553–560 https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473.

19American Psychiatric Association, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (Elsevier Masson, 2015).